[ad_1]

When looking at a picture of a sunny day at the beach, we can almost smell the scent of sun screen. Our brain often completes memories and automatically brings back to mind the different elements of the original experience. A new collaborative study between the Universities of Birmingham and Bonn now reveals the underlying mechanisms of this auto-complete function. It is now published in the journal Nature Communications.

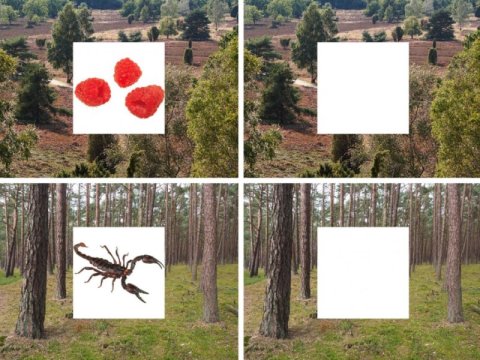

The researchers presented participants with a number of different scene images. Importantly, they paired each scene image with one of two different objects, such as a raspberry or a scorpion. Participants were given 3 seconds to memorise a given scene-object combination. After a short break they were presented with the scene images again, but now had to reconstruct the associated object image from memory.

“At the same time, we examined participants’ brain activation,” explains Prof. Florian Mormann, who heads the Cognitive and Clinical Neurophysiology group at the University of Bonn Medical Centre. “We focused on two brain regions — the hippocampus and the neighbouring entorhinal cortex.” The hippocampus is known to play a role in associative memory, but how exactly it does so has remained poorly understood.

The researchers made an exciting discovery: During memory recall, neurons in the hippocampus began to fire strongly. This was also the case during a control condition in which participants only had to remember scene images without the objects. Importantly, however, hippocampal ativity lasted much longer when participants also had to remember the associated object (the raspberry or scorpion image). Additionally, neurons in the entorhinal cortex began to fire in parallel to the hippocampus.

“The pattern of activation in the entorhinal cortex during successful recall strongly resembled the pattern of activation during the initial learning of the objects,” explains Dr. Bernhard Staresina from the University of Birmingham. Indeed, the similarity between recall and learning was so strong that a computer algorithm was able to tell whether the participant remembered the raspberry or the scorpion. “We call this process reinstatement,” Staresina says: “The act of remembering put neurons in a state that strongly resembles their activation during initial learning.”

The researchers think that such reinstatement is driven by neurons in the hippocampus. Like a librarian, hippocampal neurons might provide pointers telling the rest of the brain where particular memories (such as the raspberry and the scorion) are stored.

Looking into the brain of Epilepsy patients

The brain recordings were conducted at the University Clinic of Epileptology in Bonn — one of Europe’s biggest epilepsy centres. The clinic specialises on patients who suffer from severe forms of medial temporal lobe epilepsy. The goal is to surgically remove those parts of the brain that cause the epileptic seizures. In order to localise the origin of the seizures, some patients are implanted with electrodes. These electrodes are able to record brain activation. Researchers can use this rare opportunity to closely monitor the brain while it remembers.

This is also what the current study did: The 16 participants were all epilepsy patients who had small electrodes implanted in their medial temporal lobe. “With these electrodes we were able to record the neurons’ response to visual stimuli,” Prof. Mormann explains. These methods allows fascinating insights into the mechanisms of our memory system. They might also be used to better understand the causes for memory deficits.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Bonn. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]