[ad_1]

Drinking water from wells in rural north central Pennsylvania had low levels of pharmaceuticals, according to a study led by Penn State researchers.

Partnering with volunteers in the University’s Pennsylvania Master Well Owner Network, researchers tested water samples from 26 households with private wells in nine counties in the basin of the West Branch of the Susquehanna River. All samples were analyzed for seven over-the-counter and prescription pharmaceuticals: acetaminophen, ampicillin, caffeine, naproxen, ofloxacin, sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim.

At least one compound was detected at all sites. Ofloxacin and sulfamethoxazole — antibiotics prescribed for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections — were the most frequently detected compounds. Caffeine was detected in approximately half of the samples, while naproxen — an anti-inflammatory drug used for the management of pain, fever and inflammation — was not detected in any samples.

“It is now widely known that over-the-counter and prescription medications are routinely present at detectable levels in surface and groundwater bodies,” said Heather Gall, assistant professor of agricultural and biological engineering, whose research group in the Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences conducted the study. “The presence of these emerging contaminants has raised both environmental and public health concerns, particularly when these water supplies are used as drinking water sources.”

The good news, Gall pointed out, is that the concentrations of the pharmaceuticals in groundwater sampled were extremely low — at parts per billion levels. However, given that sampling with the Master Well Owner Network only occurred once, the frequency of occurrence, range of concentrations and potential health risks are not yet well understood, especially for these private groundwater supplies.

The researchers used a simple modeling approach based on the pharmaceuticals’ physicochemical parameters — degradation rates and sorption factors — to provide insight into the differences in frequency of detection for the target pharmaceuticals, noted lead researcher Faith Kibuye, who will graduate with a doctoral degree in biorenewable systems next year.

She explained that calculations revealed that none of the concentrations observed in the groundwater wells posed any significant human health risk, with risk quotients that are well below the minimal value. However, the risk assessment does not address the potential effect of exposure to mixtures of pharmaceuticals that are likely present in water simultaneously, she said. For example, as many as six of the analyzed pharmaceuticals were detected in some groundwater samples.

“There remains a major concern that even at low concentrations, pharmaceuticals could interact together and influence the biochemical functioning of the human body, so even at very low concentrations they might have some kind of synergistic effect,” Kibuye said. “We only analyzed for seven pharmaceuticals but the chances are that there may have been many more.”

The findings of the research — which Kibuye will present today (July 31) at the annual meeting of the American Association of Agricultural and Biological Engineers in Detroit — should be of interest the world over because groundwater is a critical supply of drinking water globally.

It is estimated that half of the population accesses potable water from groundwater aquifers. In the United States, approximately 13 million households use private wells as their drinking water source, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. In Pennsylvania, approximately one-third of the residents receive their drinking water from private groundwater wells, Penn State Extension surveys show.

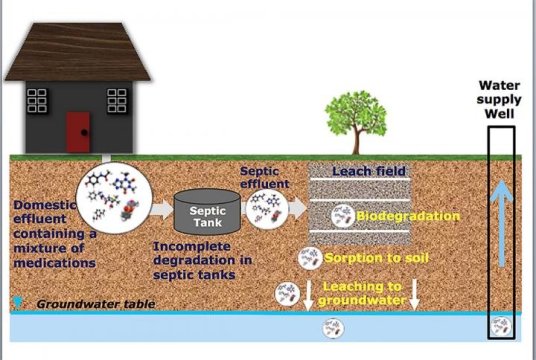

It is common for homeowners with private wells to also have septic tanks on their properties for treatment of their wastewater. And while septic tanks are generally installed downgradient of the well, it is possible that contaminant from septic systems can impact well-water quality, especially if the septic systems are not maintained or were improperly installed.

“While common contaminant issues include fecal coliform, E. coli and nitrate, pharmaceuticals and other compounds of emerging concern pose potential threats to well water quality,” Kibuye said. “Pharmaceuticals that are incompletely degraded in septic tanks and leaching fields can therefore travel with wastewater plumes and impact groundwater, potentially making septic systems important point sources to surrounding domestic groundwater sources.”

Story Source:

Materials provided by Penn State. Original written by Jeff Mulhollem. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]