[ad_1]

As little as one hour of exposure to tobacco smoke per week can significantly impact the health of teens, according to a University of Cincinnati study published in the September 2018 issue of Pediatrics.

“There is no safe level of secondhand smoke exposure,” says Ashley Merianos, the lead author of the study and an assistant professor in UC’s School of Human Services. “Even a small amount of exposure can lead to more emergency department visits and health problems for teens. That includes not just respiratory symptoms, but lower overall health.”

The study, “Adolescent Tobacco Smoke Exposure, Respiratory Symptoms, and Emergency Department Utilization,” used data from a 2014-15 national survey that looks at tobacco use and related health issues among U.S. people 12 years old and above. A total of 7,389 nonsmoking teens without asthma were included in the study.

The study found that teens exposed to tobacco smoke were at higher risk of having respiratory symptoms, such as shortness of breath and a dry cough at night. It also found that smoke-exposed teens were more likely to seek treatment at an urgent care or hospital emergency department.

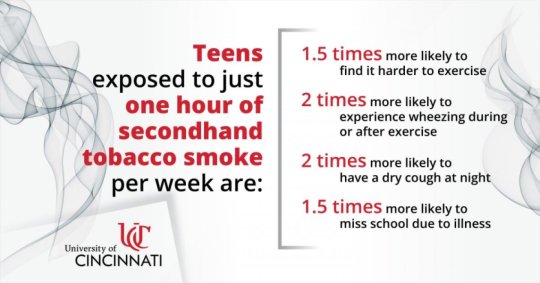

The study also found that adolescents exposed to tobacco smoke were more likely to find it hard to exercise, including wheezing during and after exercise. They were also found to be more likely to report that they frequently missed school due to illness than unexposed teens.

The American Academy of Pediatrics — which publishes Pediatrics — considers tobacco use a pediatric disease due to the negative health effects associated with secondhand smoke exposure. Despite significant progress in tobacco control, over one-third (35 percent) of U.S. nonsmoking adolescents without asthma were exposed to tobacco smoke for an hour or more within the prior seven days, according to the study.

Teens exposed to just one hour of secondhand smoke per week are: 1.5 times more likely to find it harder to exercise; two times more likely to experience wheezing during or after exercise; two times more likely to have a dry cough at night; and 1.5 times more likely to miss school due to illness.

Merianos concluded that more must be done to curb adolescent exposure to secondhand smoke. “Healthcare providers or other health professionals can offer counseling to parents and other family members who smoke to help them quit smoking, and parents should be counseled on how to prevent and reduce their adolescent’s secondhand smoke exposure,” she says. “Also, health professionals should educate teens on the dangers associated with tobacco use to prevent initiation.”

Merianos calls for medical professionals to follow “the 5 A’s,” the evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for treating tobacco use and dependence:

- Ask about tobacco use during every teen’s visit;

- Advise the teen or family member to quit;

- Assess the willingness of the teen or family member to make an attempt to quit;

- Assist the willing teen or family member with an attempt to quit by offering medication, counseling and/or supplementary materials including hotline information; and

- Arrange for a follow-up visit or contact.

“Additionally, health professionals can help parents and family members establish home and car smoking bans,” Merianos says.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Cincinnati. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]