[ad_1]

Researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine have discovered using mice and human clinical specimens, that caspase-2, a protein-cleaving enzyme, is a critical driver of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a chronic and aggressive liver condition. By identifying caspase-2’s critical role, they believe an inhibitor of this enzyme could provide an effective way to stop the pathogenic progression that leads to NASH — and possibly even reverse early symptoms.

The findings are published in the September 13 online issue of Cell.

“Our results show that caspase-2 is a critical mediator of NASH pathogenesis, not only in mice but probably in humans as well,” said Michael Karin, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Pharmacology at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “While explaining how NASH is initiated, our findings also offer a simple and effective way to treat or prevent this devastating disease.”

NASH is the most aggressive form of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which includes a spectrum of chronic liver diseases and has become a leading cause of liver transplants. The cause of both NAFLD and NASH remains a mystery, but researchers believe one factor that accelerates the progression of benign NAFLD to aggressive NASH is elevated endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, induced by protein misfolding within the liver. This results in excessive buildup of cholesterol and triglycerides in liver tissue.

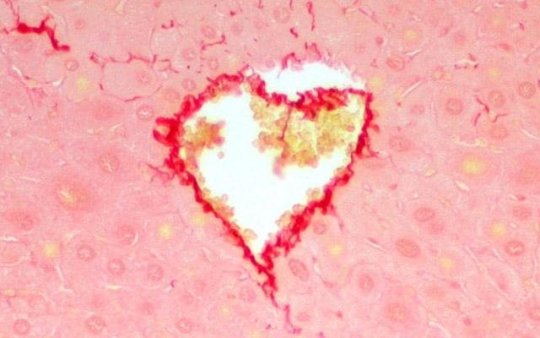

Applying this premise in mice, researchers first identified molecules involved in NASH pathogenesis by combining liver-specific ER stress and a high-fat diet to elicit NASH like disease, duplicating the cardinal features of human NASH, including fat accumulation in liver cells, liver damage, inflammation and scarring. Using this model, researchers found that the onset of NASH correlated with increased expression of caspase-2.

In the next phase, Karin and team examined human liver specimens collected from patients with benign NAFLD or aggressive NASH to confirm caspase-2 expression was also elevated in humans. By knocking out the caspase-2 gene in mice subjected to liver ER stress and high-fat diet or treating the mice with a specific caspase-2 inhibitor, they found that caspase-2 was responsible for all aspects of NASH, including lipid droplet accumulation, liver damage, inflammation and scarring.

“We now know that by preventing caspase-2 expression or inhibiting its activity that biomarkers of NASH are mitigated,” said Juyoun Kim, PhD, senior fellow in the Karin laboratory and lead author. “This is exciting because now, we not only understand the role of caspase-2 in the disease, but also have a new avenue to find a potential drug treatment.”

Through this study, Karin and team also discovered that caspase-2 has a critical role in activating SREBP1 and 2 — the master regulators of lipogenesis, a process that takes place in the liver where nutrients like carbohydrates are turned into fatty acids, triglycerides and cholesterol. Caspase-2 was found to control SREBP1 and 2 activation by cleaving another protein called site-1 protease.

“In NASH-free individuals, the activities of SREBP1 and SREBP2 are kept under control, which is essential for preventing excessive lipid accumulation in the liver,” said Karin. “However, in NASH patients, something goes awry and the liver continues to turn out excess amounts of triglycerides and cholesterol. This correlates with elevated SREBP1 and SREBP2 activities and increased caspase-2 expression.”

Moving forward, Karin and team would like to embark on development of more effective drug-like caspase-2 inhibitors that could be used for NASH prevention, and ultimately provide a treatment option.

“This study was a great step forward in being able to understand the causes, and explore possible new treatments for patients with NASH and NAFLD,” said co-author Rohit Loomba, MD, director of the UC San Diego NAFLD Research Center and director of hepatology at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “It is our hope to eventually translate and validate these study results using a much larger cohort of human subjects.”

“This study was a great step forward in being able to understand the causes, and explore possible new treatments for patients with NASH and NAFLD,” said co-author Rohit Loomba, MD, director of the UC San Diego NAFLD Research Center and director of hepatology at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “It is our hope to eventually translate and validate these study results using a much larger cohort of human subjects.”

Co-authors include: Ricard Garcia-Carbonell, Shinichiro Yamachika, Peng Zhao, Debanjan Dhar and Alan R. Saltiel, all UC San Diego; and Randal J. Kaufman, Sanford-Burnham-Prebys Medical Discovery Institute.

[ad_2]