[ad_1]

Melbourne researchers have discovered a way to halt the invasion of the toxoplasmosis-causing parasite into cells, depriving the parasite of a key factor necessary for its growth.

The findings are a key step in getting closer to a vaccine to protect pregnant women from the parasite Toxoplasma gondii, which carries a serious risk of miscarriage or birth defects. The parasite is common in Australia, being carried by 30 per cent of the Australian population, and is transmitted by cat faeces and can also be acquired from raw meat. Toxoplasma infection may also have a link to neurological disorders such as schizophrenia.

The research, published today in the journal PLOS Biology, was led by Associate Professor Chris Tonkin, Dr Alex Uboldi and Ms Mary-Louise Wilde from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

At a glance

- The parasite Toxoplasma gondii is carried by 30 per cent of the Australian population, and is a significant cause of miscarriage and birth defects.

- Walter and Eliza Hall Institute researchers have discovered that a factor called protein kinase A (PKA) is required for Toxoplasma gondii to invade a host cell.

- The finding could lead to a vaccine or treatment for Toxoplasmosis, and sheds light on more general processes involved in other diseases caused by related parasites such as malaria.

- The breakthrough was possible through use of high-quality imaging facilities at the Institute’s Centre for Dynamic Imaging.

Cut the brakes

There are two important steps allowing Toxoplasma gondii to take hold within our body: the parasite needs to enter a host cell, and from there it replicates and spreads.

“After Toxoplasma infects humans it needs to switch off the infection machinery and switch on replication,” Associate Professor Tonkin said. ‘Without the ability to do this, Toxoplasma will die and be unable to cause disease. We discovered that the gene protein kinase A (PKA) is required for this switch. Without PKA, Toxoplasma can’t hold steady.”

Importance of new technology

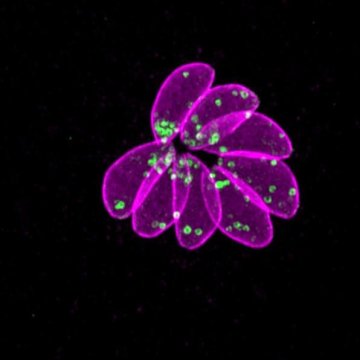

According to Dr Uboldi, the discovery was made using advanced microscopy technology available at the Institute’s Centre for Dynamic Imaging.

“It wasn’t until we observed the parasite down the microscope and studied its behaviour that we noticed something unexpected,” Dr Uboldi said.

“This was fully dependent on our access to the sophisticated equipment at the Institute’s Centre for Dynamic Imaging.

“By actually watching the process take place in real time, we had that rare Eureka moment.”

Wide-ranging implications

Ms Wilde, a PhD student at the Institute, noted that Toxoplasma gondii is closely related to parasites that cause a range of globally significant diseases, such as malaria.

“Central to all these parasites is that they need to invade host cells in order to survive,” Ms Wilde said.

“Understanding the role that PKA plays in the Toxoplasma lifecycle could provide insights into the biology of other disease-causing parasites, such as Plasmodium, which causes malaria.

“PKA belongs to a class of molecules that are a really important drug target for other diseases such as cancer and diabetes. We now might be able to take our understanding of how PKA functions in these diseases to design new therapies for toxoplasmosis and infections caused by related parasites,” she said.

The research findings were supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council and an Australian Research Council fellowship.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]