Scientists from KU Leuven (Belgium) and the universities of Pittsburgh, Stanford, and Penn State (US) have identified fifteen genes that determine our facial features. The findings were published in Nature Genetics.

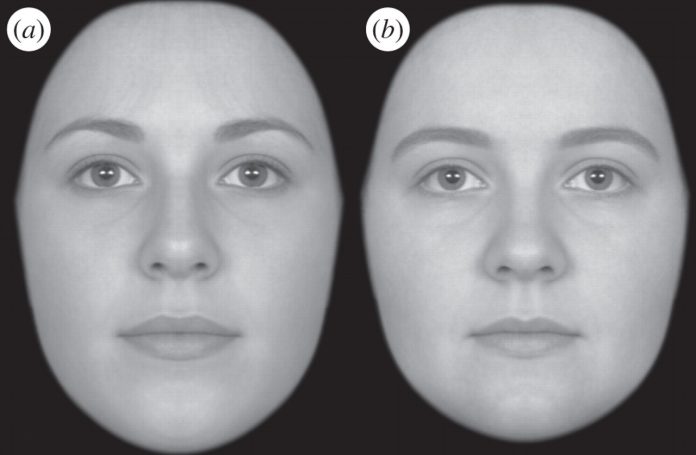

The team looked at 2,329 people of European ancestry. Their faces were modeled in 3D, which allowed the researchers to match people with similar characteristics. The team then looked for genetic similarities. They found 38 genes that might affect facial features, but only 15 of these were confirmed when they replicated the study using another 1,719 people.

“Our search doesn’t focus on specific traits,” lead author Peter Claes, from Belgium’s KU Leuven, said in a statement. “My colleagues from Pittsburgh and Penn State each provided a database with 3D images of faces and the corresponding DNA of these people. Each face was automatically subdivided into smaller modules. Next, we examined whether any locations in the DNA matched these modules. This modular division technique made it possible for the first time to check for an unprecedented number of facial features.”

The research is promising but it is in its infancy. You can’t just scan somebody’s DNA and work out what their face looks like. Even when (or if) this becomes possible, there are other factors that play a role in what we look like. Age, lifestyle, and environment, just to name a few. Understanding the genetics behind our physical characteristics is not a walk in the park.

“We’re basically looking for needles in a haystack,” added Seth Weinberg from the University of Pittsburgh. “In the past, scientists selected specific features, including the distance between the eyes or the width of the mouth. They would then look for a connection between this feature and many genes. This has already led to the identification of a number of genes but, of course, the results are limited because only a small set of features are selected and tested.”

The potential applications for this research are varied. Determining facial characteristics from genes could be used in facial reconstructive surgery and maybe even in crime scene investigations and archeological digs to work out what somebody might have looked like. The findings may also be useful as they could help us better understand how visible features are influenced by our genes.

“With the same novel technology used in this study, we can also link other medical images – such as brain scans – to genes. In the long term, this could provide genetic insight into the shape and functioning of our brain, as well as in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s,” Claes added.