[ad_1]

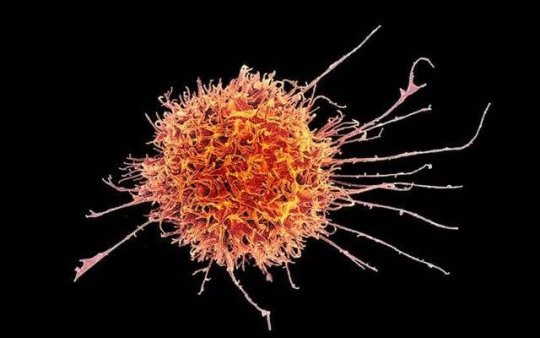

Emerging CAR-T immunotherapies leverage modified versions of patient’s T-cells to target and kill cancer cells. In a new study, published June 28 online in Cell Stem Cell, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine and University of Minnesota report that similarly modified natural killer (NK) cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) also displayed heightened activity against a mouse model of ovarian cancer.

The findings are significant, say researchers, because NK cells may offer distinct advantages over T-cells, including the ability to safely deliver engineered NK cells in an off-the-shelf manner without patient matching.

“One of the main challenges of immunotherapy has been the clinical manufacture of modified cells,” said senior author Dan Kaufman, MD, PhD, professor of medicine in the Division of Regenerative Medicine and director of cell therapy at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “We’ve shown that you can engineer iPSCs, create chimeric antigen receptor-expressing NK cells to better target refractory cancers that have resisted other treatments.”

CAR-T cell-based immunotherapies have garnered considerable attention and investment in recent years. T-cells, a type of white blood cell, are extracted from a patient’s blood, genetically modified with a chimeric antigen receptor (the CAR) to bind with a certain protein on the patient’s cancer cells, grown in large numbers in a laboratory and then infused into the patient.

“NK cells offer significant advantages as they don’t have to be matched to a specific patient,” said Kaufman. “Additionally, one batch of iPSC-derived NK cells can be potentially used to treat thousands of patients, which means we can develop standardized, ‘off-the-shelf’ treatments and use these in combination with other cancer drugs.”

Early testing of CAR-T therapies have shown promise — and sometimes dramatic success — but there are distinct limitations. First, cells must be isolated from each individual — a process that takes significant time and money. Additionally, since T-cell therapy is designed to work only for that patient, some patients may not be able to have T cells collected, or they may not have time for this process before the tumor progresses. This means some patients who could potentially benefit will not be able to get CAR-T cell-based therapies.

Moreover, Kaufman noted CAR-T therapies have been associated with sometimes severe toxicities or adverse effects, including unexpected organ damage and death. Previous research by Kaufman and others suggest NK cells do not trigger similar toxicities — and the latest paper found few adverse effects in mouse models.

“NK cells may just be safer to use,” Kaufman said. Kaufman is now collaborating with scientists from San Diego-based Fate Therapeutics to scale up processes to progress to clinical trials.

In their research, the researchers tested CAR NK cells derived from human iPSCs in an ovarian cancer xenograft mouse model, comparing their anti-tumor activity against other versions of NK cells and CAR-T cells. The former demonstrated similar activity to CAR-T cells, but with less toxicity. Kaufman said data indicated ovarian cancer was a good first target, but that other solid tumors, such as breast cancer, brain tumors, and colon cancers, as well as blood cell cancers such as leukemias are also likely to be suitable targets of iPSC-derived NK cells.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of California – San Diego. Original written by Scott LaFee. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]