A UCLA research team has shown that using a truncated form of the CD4 molecule as part of a gene therapy to combat HIV yielded superior and longer-lasting results in mouse models than previous similar therapies using the CD4 molecule.

This new approach to CAR T gene therapy — a type of immunotherapy that involves genetically engineering the body’s own blood-forming stem cells to create HIV-fighting T cells — has the potential to not only destroy HIV-infected cells but to create “memory cells” that could provide lifelong protection from infection with the virus that causes AIDS.

BACKGROUND

CAR therapies have emerged as a powerful immunotherapy for various forms of cancer and show promise for treating HIV-1, the more prevalent of the two main forms of the virus. However, current applications of these therapies may not impart long-lasting immunity. Researchers have been seeking a T cell–based therapy that can respond to malignant or infected cells that may reappear months or years after treatment.

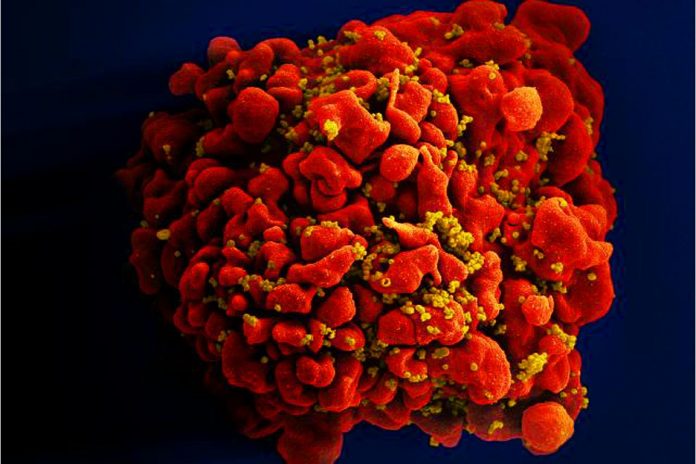

In a previous study, the UCLA researchers described the creation of blood-forming stem cells that carry genes for chimeric antigen receptors, or CARs. Once these genetically engineered stem cells are transplanted into the body, they form specialized infection-fighting white blood cells known as CAR T cells that specifically seek out and kill cells infected with HIV.

METHOD

Because HIV binds to CD4 molecules in order to infect cells in the body, the researchers previously created a CAR molecule containing part of the CD4 molecule to hijack that interaction. When HIV would bind to the CD4 section of the CAR molecule on T cells, other regions of the CAR molecule would signal the cell to become activated and kill the virus. That molecule, however, contained two parts, or “domains,” that still had the potential to allow HIV infection.

For the new study, the researchers removed those domains while adding another one that makes the cells resistant to infection and allows for a more efficient and longer-lasting cell response against HIV than before.

While the previous approach allowed for the continuous production of new HIV-fighting T cells that persisted for more than two years, these cells were essentially inactivated until they encountered HIV in the body. The improved CAR therapy engineers the body’s immune response to HIV rather than waiting for the virus — or parts of the virus — to induce a response, in much the same way vaccines prime one’s immune system to respond against a virus. The new approach also leads to the production of a significant number of “memory” T cells, that are capable of more potently and quickly responding to reactivated HIV.

IMPACT

The findings provide critical insights into the types of CAR molecules and approaches that are suitable for CAR therapies using blood-forming stem cells and that allow for optimal function and persistence of CAR T cells after development. The findings could influence the field of immunotherapy focused on engineering T cells with CAR molecules that are able to persist and form immunologic memory, and that can recognize and kill virus-infected or cancerous cells.