The swift development of vaccines has provided a vital tool to combat the spread of the deadly SARS-CoV-2 virus, but challenges to reaching herd immunity posed by the rise of new mutations and the inability of immunosuppressed people to develop an effective immune response following vaccination point to a need for additional solutions to maximize protection.

A new USC study published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry reveals how therapies targeting a molecular chaperone called GRP78 might offer additional protection against COVID-19 and other coronaviruses that emerge in the future.

Chaperones like GRP78 are molecules that help regulate the correct folding of proteins, especially when a cell is under stress. But in some cases, viruses can hijack these chaperones to infect target cells, where they reproduce and spread. GRP78 has been implicated in the spread of other serious viruses, such as Ebola and Zika.

GRP78 plays more than one role in COVID-19

While studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, infects cells by binding with ACE2 receptors on their surface, researchers from the Keck School of Medicine of USC examined whether GRP78 has a role as well.

They found that GRP78 serves as a co-receptor and stabilizing agent between ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2, enhancing recognition of the virus’ spike protein and allowing more efficient viral entry into host cells.

This study provides the first experimental evidence in support of computer modeling predictions, demonstrating that GRP78 binds the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 in cells. Interestingly, computer modeling further shows that COVID-19 variants that are more infectious bind stronger to GRP78.

Additionally, the research team found that GRP78 also binds to and acts as a regulator of ACE2 – bringing the protein to the cell surface, which offers SARS-CoV-2 more points to bind with and infect cells.

“Our study reveals that therapy targeting GRP78 could be more effective at protecting and treating people who contract COVID-19 than vaccines alone, particularly when it comes to people who can’t get the vaccine and variants that could bypass vaccine protection but still depend on GRP78 for entry and production,” said senior author Amy S. Lee, PhD, Judy and Larry Freeman Chair in basic science research and professor at the department of biochemistry & molecular medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

How SARS-CoV-2 hijacks GRP78

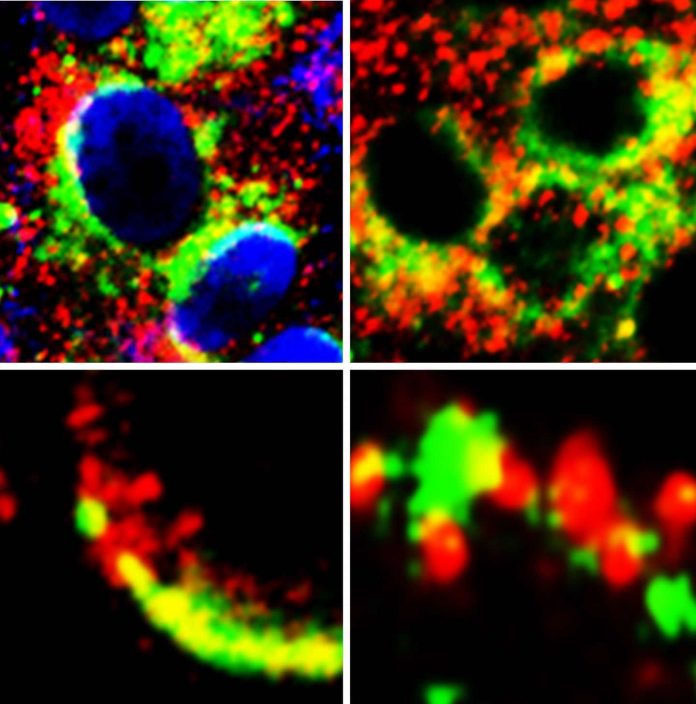

GRP78’s job as a chaperone molecule is to fold proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which is a protein production factory. Upon stress, including stress caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, GRP78 is shipped out to the cell surface. There, it facilitates binding between ACE2 and Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, leading to enhanced viral entry. Once inside the cell, viruses are known to hijack the ER protein folding machinery, of which GRP78 is a key player, to produce more viral proteins.

This process can be intensified in cells under stress from other diseases like diabetes or cancer, which may be one of the reasons people who have underlying health conditions are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

To investigate the role of GRP78 in SARS-CoV-2 infection, researchers treated lung epithelial cells with humanized monoclonal antibody (hMAb159), known to remove GRP78 from the cell surface with no adverse effects in mouse models. Intervention removed GRP78 and reduced ACE2 on the cell surface, diminishing the number of targets to which SARS-CoV-2 could attach.

These findings led researchers to conclude that interventions, such as hMAb159, to remove cell surface GRP78 could reduce SARS-CoV-2 infection and inhibit the spread and severity of COVID-19 in people who are infected.

Potential for GRP78 targeted treatment

Healthy cells need a fraction of GRP78 to function normally. However, stressed cells, such as virally infected or cancerous cells, need more GRP78 to survive and multiply, so treatments that reduce the amount of GRP78 in the body could reduce the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection and spread without adverse effects.

While this study used a monoclonal antibody, researchers say there are other agents that could be used to reduce the amount or activity of GRP78, creating multiple pathways for potential drug solutions to target GRP78.

“What is particularly exciting for this finding is that GRP78 could be a universal target in combination with existing therapies not just to combat COVID-19, but other deadly viruses that depend on GRP78 for their infectivity as well,” said Lee.

The next step for the research team is to explore these findings further through animal studies.