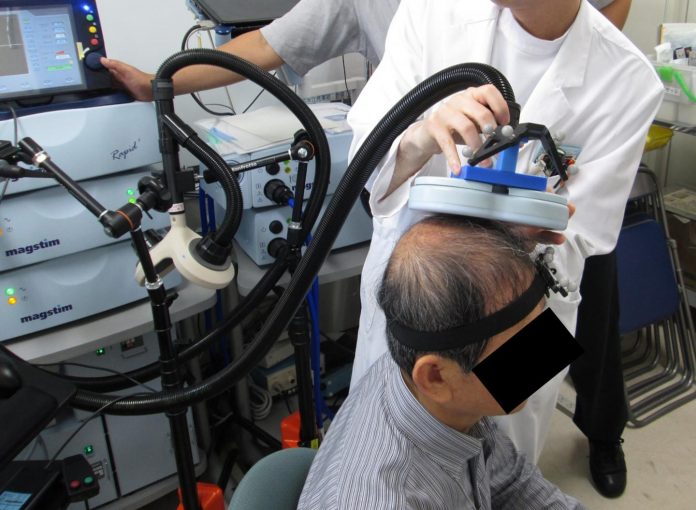

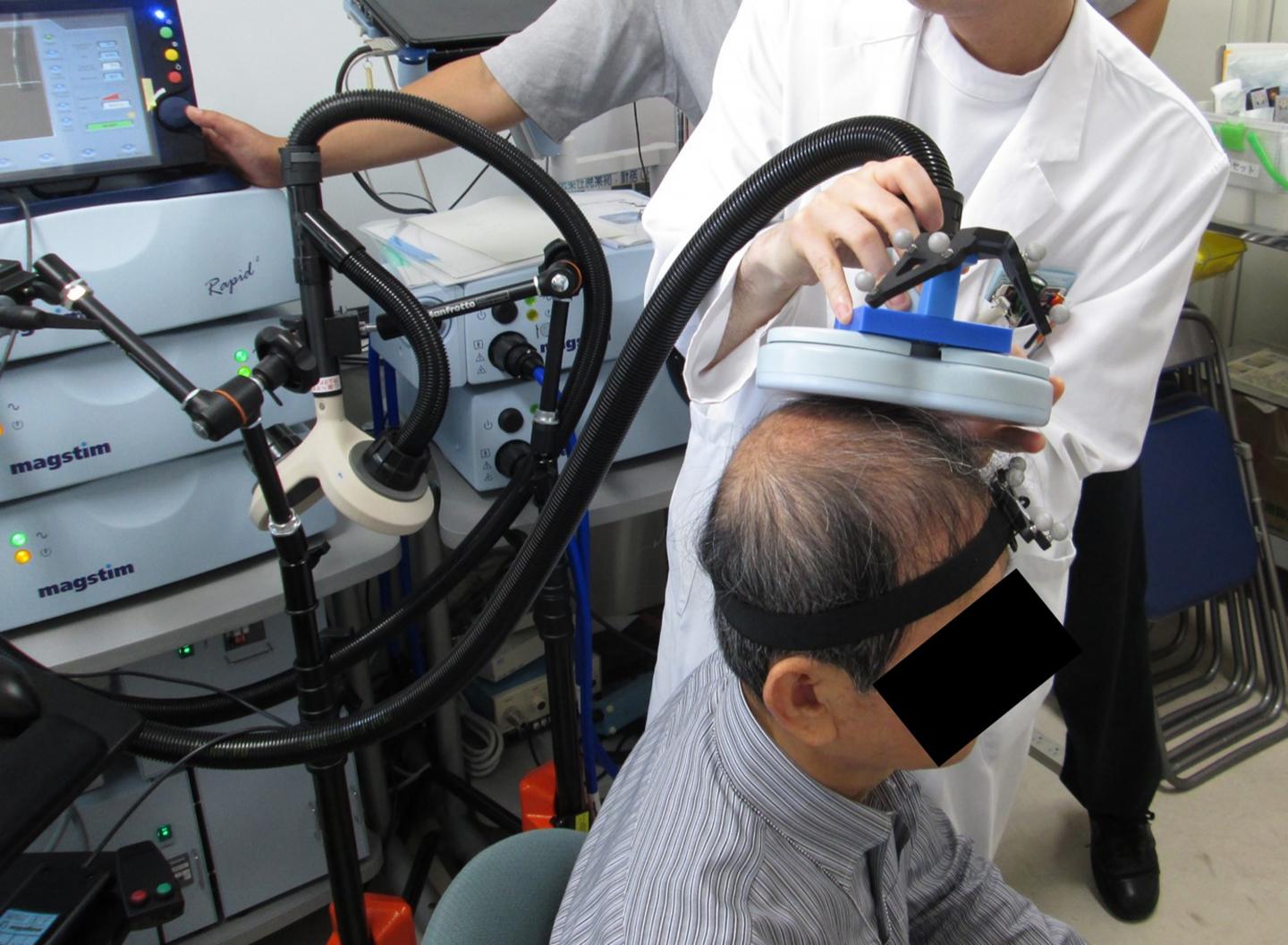

IMAGE: nrTMS involves stimulating the brain with rapid magnetic pulses to determine where the language centers are.

view more

Credit: Kazuya Motomura

A technique that maps a patient’s language centers before going into surgery works best when their brain tumor is not in those areas. The finding, published by Nagoya University researchers in the journal Scientific Reports, refines understanding of the test’s effectiveness and could help improve surgical planning.

Gliomas are a common brain tumor that require extensive removal for patient survival. They often occur in regions involved in motor and language functions, so surgeons do their best to remove the tumors while protecting these vital regions. The language center is usually on the left side of the brain, but personal differences do exist.

Currently, surgeons try to protect the language regions by keeping the patient awake during surgery–the brain does not contain pain receptors–and applying direct cortical stimulation to various points on the brain while the patient simultaneously names what they see in an image. When an area involved in language is stimulated, the patient is unable to name the image. This method is very accurate for mapping the brain’s language regions, but surgeons are looking for similarly accurate methods that can be done before an operation. This would help surgical planning and improve the prospects of the procedure.

Surgeons are experimenting with navigated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (nrTMS) for language mapping. Before surgery, rapid magnetic stimulating pulses are applied to the head while the patient names what they see in images. However, the procedure’s accuracy varies. Nagoya University neurosurgeon Kazuya Motomura and colleagues wanted to know why.

They analyzed how different clinical parameters, such as age, tumor type, tumor volume, and tumor involvement in the language centers, affect nrTMS accuracy in language mapping. They conducted nrTMS on 42 people with low grade and 19 with high grade gliomas. The tumor was in the left hemisphere in 50 patients and in the right in 11.

The factor that significantly impacted the procedure’s accuracy in language center mapping was tumor involvement in these centers. Otherwise, nrTMS showed a good degree of reliability. The scientists also successfully used nrTMS to determine the side of the brain where the language center is mainly located in each patient.

“Our findings suggest that nrTMS language mapping could be a reliable method, particularly when the tumor is not involved in the classical language areas,” says Motomura.

The approach needs further validation by testing it on larger numbers of patients in a randomized study.

###

The paper, “Navigated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as preoperative assessment in patients with brain tumors,” was published in the journal Scientific Reports on June 3, 2020 at DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-65944-8

About Nagoya University, Japan

Nagoya University has a history of about 150 years, with its roots in a temporary medical school and hospital established in 1871, and was formally instituted as the last Imperial University of Japan in 1939. Although modest in size compared to the largest universities in Japan, Nagoya University has been pursuing excellence since its founding. Six of the 18 Japanese Nobel Prize-winners since 2000 did all or part of their Nobel Prize-winning work at Nagoya University: four in Physics – Toshihide Maskawa and Makoto Kobayashi in 2008, and Isamu Akasaki and Hiroshi Amano in 2014; and two in Chemistry – Ryoji Noyori in 2001 and Osamu Shimomura in 2008. In mathematics, Shigefumi Mori did his Fields Medal-winning work at the University. A number of other important discoveries have also been made at the University, including the Okazaki DNA Fragments by Reiji and Tsuneko Okazaki in the 1960s; and depletion forces by Sho Asakura and Fumio Oosawa in 1954.

TDnews