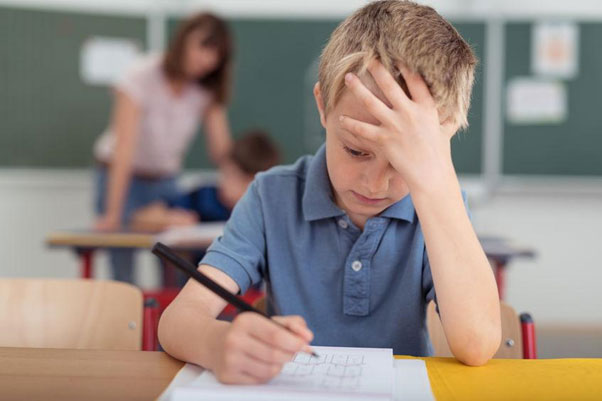

Parents’ high hopes for their children’s academic achievement can actually harm their school performance, suggests a new study. The research found that if parents’ expectations exceed their child’s ability, poor scholastic performance may follow.

“Our research revealed both positive and negative aspects of parents’ aspiration for their children’s academic performance. Although parental aspiration can help improve children’s academic performance, excessive parental aspiration can be poisonous,” lead author Kou Murayama, PhD, of the U.K.’s University of Reading’s School of Psychology and Clinical Language Services, said in a news release.

For the study, Murayama and his colleagues analyzed data from a 2002 to 2007 German study of 3,530 students ages 11 to 16. The researchers looked at the students’ math grades and asked their parents to assess their aspirations for their child – how much they wanted their child to get a certain grade – and their expectations for their child – how much they believed their child could get that grade.

Findings showed that high parental aspirations led to increased academic achievement, but only when it did not overly exceed realistic expectations. When expectations exceeded the child’s ability, academic achievement fell.

The researchers were able to replicate the main findings of the German study using data from a two-year study of over 12,000 U.S. 15-year-old students and their parents. The results matched those of their study, providing further evidence of the negative effects of parents’ unrealistic expectations on a child’s academic achievement.

Murayama told The Telegraph that parents’ unrealistic goals and the pressure to achieve might cause children to experience anxiety, low confidence and frustration. He suggested that overbearing parents who aim too high may also exert too much control over their children with detrimental results.

Although previous psychological studies have linked high parental aspirations with children’s academic achievement, the new study highlights an exception. “Much of previous literature conveyed a simple, straightforward message – aim high for your children and they will achieve more. In fact, getting parents to have higher hopes for their children has often been the goal of programs designed to improve academic performance in schools,” said Murayama in the news release.

“This study suggests that the focus of such educational programs should not be on blindly increasing parental aspirations but on giving parents the information they need to develop realistic expectations,” Murayama added. “Unrealistically high aspirations may hinder academic performance. Simply raising aspirations cannot be an effective solution to improve success in education.”