Dementias are characterised by the build-up of different types of protein in the brain, which damages brain tissue and leads to cognitive decline. In the case of Alzheimer’s disease, these proteins include beta-amyloid, which forms ‘plaques’, clumping together between neurons and affecting their function, and tau, which accumulates inside neurons.

Molecular and cellular changes to the brain usually begin many years before any symptoms occur. Diagnosing dementia can take many months or even years. It typically requires two or three hospital visits and can involve a range of CT, PET and MRI scans as well as invasive lumber punctures.

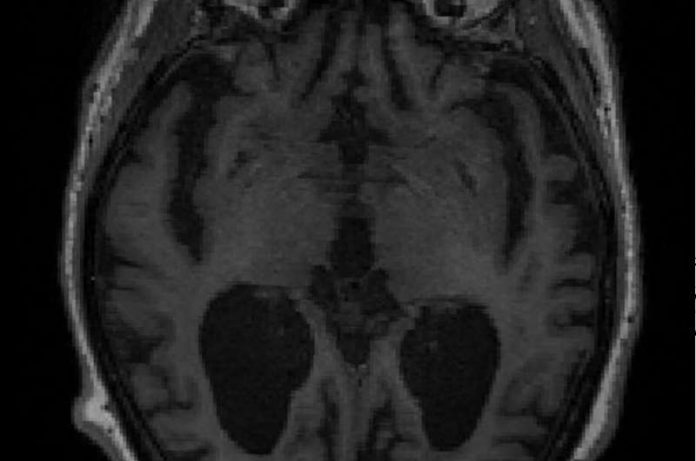

A team led by Professor Zoe Kourtzi at the University of Cambridge and The Alan Turing Institute has developed machine learning tools that can detect dementia in patients at a very early stage. Using brain scans from patients who went on to develop Alzheimer’s, their machine learning algorithm learnt to spot structural changes in the brain. When combined with the results from standard memory tests, the algorithm was able to provide a prognostic score – that is, the likelihood of the individual having Alzheimer’s disease.

For those patients presenting with mild cognitive impairment – signs of memory loss or problems with language or visual/spatial perception – the algorithm was higher than 80% accurate in predicting those individuals who went on to develop Alzheimer’s disease. It was also able to predict how fast their cognition will decline over time.

Professor Kourtzi, from Cambridge’s Department of Psychology, said: “We have trained machine learning algorithms to spot very early signs of dementia just by looking for patterns of grey matter loss – essentially, wearing away – in the brain. When we combine this with standard memory tests, we can predict whether an individual will show slower or faster decline in their cognition.

“We’ve even been able to identify some patients who were not yet showing any symptoms, but went on to develop Alzheimer’s.”

“In time, we hope to be able to identify patients as early as five to ten years before they show symptoms as part of a health check.”

Although the algorithm has been optimised to look for signs of Alzheimer’s disease, Professor Kourtzi and colleagues are now training it to recognise different forms of dementia, each of which has its own characteristic pattern of volume loss.

Dr Timothy Rittman from the Department of Clinical Neurosciences and a consultant at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, part of Cambridge University Hospitals (CUH) NHS Foundation Trust, is now leading a trial to look at whether this approach is useful in a clinical setting.

“We’ve shown that this approach works in a research setting – we now need to test it in a ‘real world’ setting,” explained Dr Rittman.

To date around 80 patients have taken part in the trial, which was run by CUH, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust and two NHS trusts in Brighton.

Catching dementia early is important for several reasons, explained Dr Rittman. “When patients begin to experience memory and cognitive problems, this can understandably be a very difficult time. Being able to provide an accurate diagnosis gives them clarity and, depending on the diagnosis, can either ease their minds or help them and their loved ones put preparations in place for the longer term.”

“If we catch the disease early enough, there are lifestyle changes we can recommend – blood pressure medication, improved diet and exercise, stopping smoking, for example – that may help slow the progression of the disease.”

Dr Timothy Rittman

There are currently very few drugs available to help treat dementia. One of the reasons that clinical trials often fail is thought to be because once a patient has developed symptoms, it may be too late to make a major difference. Having the ability to identify individuals at a very early stage could therefore help researchers develop new medicines.

If the trial is successful, the algorithm could be rolled out to thousands more patients across the country.