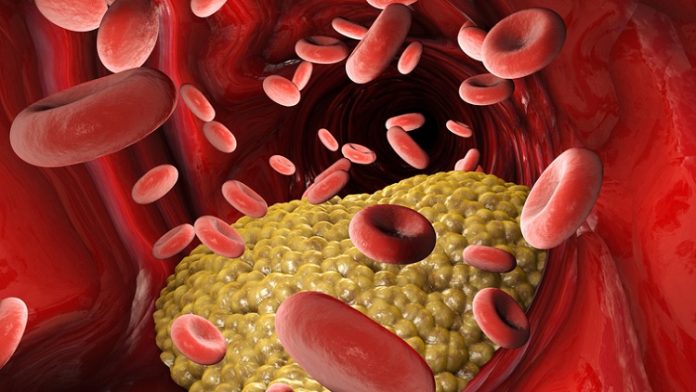

For decades, elevated cholesterol levels have been blamed for the risk of heart attacks and strokes. Now, a new study reports that intestinal bacteria may be the culprit. These bacteria turn lecithin, a component of egg yolks, liver, beef, pork, and wheat germ, into an artery-clogging compound called TMAO. The research may lead to preventative and predictive measures for cardiovascular disease. Investigators affiliated with the Cleveland Clinic (Cleveland Ohio) published their findings in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In addition to implicating certain bacteria in cardiovascular disease risk, they also found that blood levels of TMAO predict heart attack, stroke or death, and do so “independent of other risk factors,” noted lead researcher Dr Stanley Hazen, chairman of cellular and molecular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic’s Lerner Research Institute. The findings may lead to a TMAO test being included in tests used to predict heart disease.

The study authors noted that recent studies in animals have shown a link between intestinal microbial metabolism of lecithin and coronary artery disease through the production of a proatherosclerotic (atherosclerosis-causing) metabolite, trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO). They investigated the relationship among intestinal bacteria-dependent metabolism of dietary lecithin, TMAO levels, and adverse cardiovascular events in humans.

The investigators measured plasma and urinary levels of TMAO and plasma choline and betaine levels by means of liquid chromatography and online tandem mass spectrometry after a lecithin challenge (ingestion of two hard-boiled eggs and deuterium [d9]-labeled phosphatidylcholine (lecithin)) in healthy individuals before and after the suppression of intestinal bacteria with oral broad-spectrum antibiotics. In addition, they examined the relationship between fasting plasma levels of TMAO and major adverse cardiovascular events (death, myocardial infarction, or stroke) during three years of follow-up in 4,007 patients undergoing elective coronary angiography.

The researchers found time-dependent increases in levels of both TMAO and its d9 isotopologue, as well as other choline metabolites after the lecithin challenge. Plasma levels of TMAO were markedly suppressed after the administration of antibiotics and then reappeared after withdrawal of antibiotics. Increased plasma levels of TMAO were associated with an increased risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event. Individuals in the top 25 percent of TMAO levels had 2.5 times the risk of a heart attack or stroke compared to individuals in the bottom quartile. An elevated TMAO level predicted an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events after adjustment for traditional risk factors, as well as in lower-risk subgroups.

The authors concluded that the production of TMAO from dietary lecithin is dependent on metabolism by the intestinal bacteria. Increased TMAO levels are associated with an increased risk of incident major adverse cardiovascular events.

Earlier this month, the same researchers reported that intestinal bacteria also transform carnitine, a nutrient found in red meat and dairy products, into TMAO, at least in meat eaters. Vegetarians made much less TMAO even when eating carnitine as part of the study, suggesting that avoiding meat reduces the gut bacteria that turn carnitine into TMAO, while regular helpings of dead animals encourages their growth and thus the production of TMAO. The researchers note that further studies are needed to show whether TMAO reliably predicts cardiovascular events, and does so better than other blood tests.