A new study suggests that all living snakes evolved from a handful of species that survived the giant asteroid impact that wiped out the dinosaurs and most other living things at the end of the Cretaceous. The authors say that this devastating extinction event was a form of ‘creative destruction’ that allowed snakes to diversify into new niches, previously filled by their competitors.

The research, published in Nature Communications, shows that snakes, today including almost 4000 living species, started to diversify around the time that an extra-terrestrial impact wiped out the dinosaurs and most other species on the planet.

The study, led by scientists at the University of Bath and including collaborators from Bristol, Cambridge and Germany, used fossils and analysed genetic differences between modern snakes to reconstruct snake evolution. The analyses helped to pinpoint the time that modern snakes evolved.

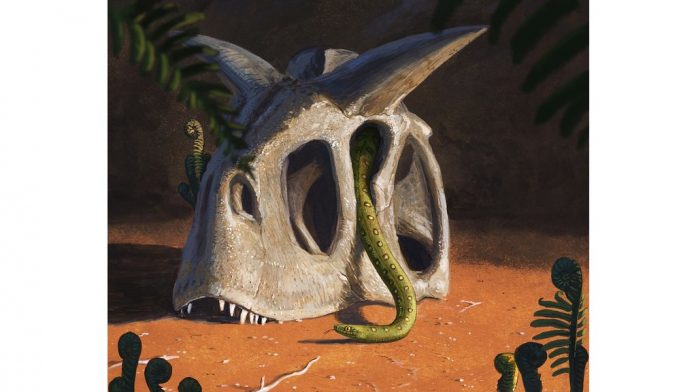

Their results show that all living snakes trace back to just a handful of species that survived the asteroid impact 66 million years ago, the same extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs.

The authors argue that the ability of snakes to shelter underground and go for long periods without food helped them survive the destructive effects of the impact. In the aftermath, the extinction of their competitors – including Cretaceous snakes and the dinosaurs themselves – allowed snakes to move into new niches, new habitats and new continents.

Snakes then began to diversify, producing lineages like vipers, cobras, garter snakes, pythons, and boas, exploiting new habitats, and new prey. Modern snake diversity – including tree snakes, sea snakes, venomous vipers and cobras, and huge constrictors like boas and pythons – emerged only after the dinosaur extinction.

Fossils also show a change in the shape of snake vertebrae in the aftermath, resulting from the extinction of Cretaceous lineages and the appearance of new groups, including giant sea snakes up to 10 metres long.

“It’s remarkable, because not only are they surviving an extinction that wipes out so many other animals, but within a few million years they are innovating, using their habitats in new ways,” said lead author and recent Bath graduate Dr Catherine Klein, who now works at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU) in Germany.

The study also suggests that snakes began to spread across the globe around this time. Although the ancestor of living snakes probably lived somewhere in the Southern Hemisphere, snakes first appear to have spread to Asia after the extinction.

Dr Nick Longrich, from the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath and the corresponding author, said: “Our research suggests that extinction acted as a form of ‘creative destruction’- by wiping out old species, it allowed survivors to exploit the gaps in the ecosystem, experimenting with new lifestyles and habitats.

“This seems to be a general feature of evolution – it’s the periods immediately after major extinctions where we see evolution at its most wildly experimental and innovative.

“The destruction of biodiversity makes room for new things to emerge and colonize new landmasses. Ultimately life becomes even more diverse than before.”

The study also found evidence for a second major diversification event around the time that the world shifted from a warm ‘Greenhouse Earth’ into a cold ‘Icehouse’ climate, which saw the formation of polar icecaps and the start of the Ice Ages.

The patterns seen in snakes hint at a key role for catastrophes – severe, rapid, and global environmental disruptions – in driving evolutionary change.