Scientists have discovered a new species of marsupial lion, that is believed to have been extinct for at least 19 million years.

The study, published in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, identifies the new species from 19-million-year-old fossilised remains discovered in Queensland comprising an almost complete skull, teeth, and upper arm bones.

“It is very rare to get a complete skull of a marsupial lion that is this old, so this specimen is a real treasure,” says Dr Anna Gillespie from the University of New South Wales in Sydney, lead author of the paper.

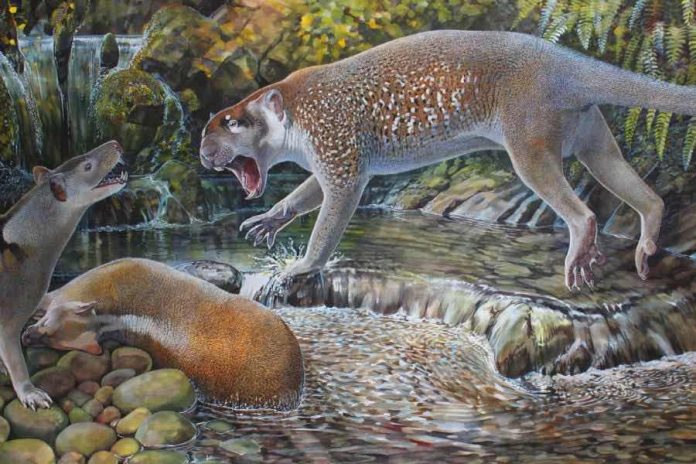

Dubbed Wakaleo schouteni, the dog-sized predator was armed with the ferocious blade-like teeth characteristic of marsupial lions, perfect for slicing up the flesh of its prey – such as lizards, birds, frogs and small possums.

By studying at its teeth in a spot of palaeontological dentistry, the researchers also discerned that the species likely enjoyed small servings of vegetables.

Marsupial lions are the largest meat-eating mammals ever to have existed in Australia, but are unrelated to today’s predators on the savannas of Africa.

This new species lived between 26 and 18 million years ago in the late Oligocene and the early Miocene, meaning that it must have been a contemporary of another species of marsupial lion, the slightly smaller Wakaleo pitikantensis.

W. schouteni is also an ancient cousin of Thylacoleo carnifex, a powerful, highly specialised carnivore that roamed the continent until 40,000 years ago. Weighing only 23 kg, this new species is about one fifth of the weight of its better-studied relative, but is enormous compared to another family member: Microleo attenboroughi, a kitten-sized marsupial lion discovered at the same fossil site last year.

The remains of this unique species were found in northwest Queensland in one of the world’s most important and abundant fossils deposits, the Riversleigh World Heritage Site. This remote cache has also revealed fossils of Tasmanian Tigers, a carnivorous kangaroo, a flightless bird like a cross between an emu and a cassowary, a goanna-like crocodile and tree-dwelling marsupial cats. Most of the remains are from a period between 25 and 15 million years ago, giving researchers a window into the evolutionary timeline of many species.

The discovery of W. schouteni raises new questions about family ties on an evolutionary scale, says Gillespie. “The identification of these new species has brought to light a level of marsupial lion diversity that was quite unexpected and suggests even deeper origins for the family.”

The missing parts of the remains leave Gillespie with more mysteries to investigate: “What were its limbs, hands and feet like? Did it have a long or a short tail? We only have a few bones of the rest of the skeleton so it’s going to take some time to answer these questions.”