[ad_1]

A piping hot planet discovered by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) has pointed the way to additional worlds orbiting the same star, one of which is located in the star’s habitable zone. If made of rock, this planet may be around twice Earth’s size.

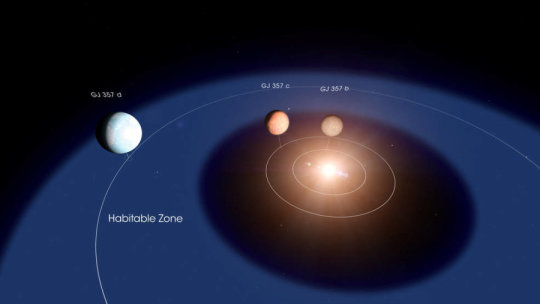

The new worlds orbit a star named GJ 357, an M-type dwarf about one-third the Sun’s mass and size and about 40% cooler that our star. The system is located 31 light-years away in the constellation Hydra. In February, TESS cameras caught the star dimming slightly every 3.9 days, revealing the presence of a transiting exoplanet — a world beyond our solar system — that passes across the face of its star during every orbit and briefly dims the star’s light.

“In a way, these planets were hiding in measurements made at numerous observatories over many years,” said Rafael Luque, a doctoral student at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands (IAC) on Tenerife who led the discovery team. “It took TESS to point us to an interesting star where we could uncover them.”

The transits TESS observed belong to GJ 357 b, a planet about 22% larger than Earth. It orbits 11 times closer to its star than Mercury does our Sun. This gives it an equilibrium temperature — calculated without accounting for the additional warming effects of a possible atmosphere — of around 490 degrees Fahrenheit (254 degrees Celsius).

“We describe GJ 357 b as a ‘hot Earth,'” explains co-author Enric Pallé, an astrophysicist at the IAC and Luque’s doctoral supervisor. “Although it cannot host life, it is noteworthy as the third-nearest transiting exoplanet known to date and one of the best rocky planets we have for measuring the composition of any atmosphere it may possess.”

But while researchers were looking at ground-based data to confirm the existence of the hot Earth, they uncovered two additional worlds. The farthest-known planet, named GJ 357 d, is especially intriguing.

“GJ 357 d is located within the outer edge of its star’s habitable zone, where it receives about the same amount of stellar energy from its star as Mars does from the Sun,” said co-author Diana Kossakowski at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. “If the planet has a dense atmosphere, which will take future studies to determine, it could trap enough heat to warm the planet and allow liquid water on its surface.”

Without an atmosphere, it has an equilibrium temperature of -64 F (-53 C), which would make the planet seem more glacial than habitable. The planet weighs at least 6.1 times Earth’s mass, and orbits the star every 55.7 days at a range about 20% of Earth’s distance from the Sun. The planet’s size and composition are unknown, but a rocky world with this mass would range from about one to two times Earth’s size.

Even through TESS monitored the star for about a month, Luque’s team predicts any transit would have occurred outside the TESS observing window.

GJ 357 c, the middle planet, has a mass at least 3.4 times Earth’s, orbits the star every 9.1 days at a distance a bit more than twice that of the transiting planet, and has an equilibrium temperature around 260 F (127 C). TESS did not observe transits from this planet, which suggests its orbit is slightly tilted — perhaps by less than 1 degree — relative to the hot Earth’s orbit, so it never passes across the star from our perspective.

To confirm the presence of GJ 357 b and discover its neighbors, Luque and his colleagues turned to existing ground-based measurements of the star’s radial velocity, or the speed of its motion along our line of sight. An orbiting planet produces a gravitational tug on its star, which results in a small reflex motion that astronomers can detect through tiny color changes in the starlight. Astronomers have searched for planets around bright stars using radial velocity data for decades, and they often make these lengthy, precise observations publicly available for use by other astronomers.

Luque’s team examined ground-based data stretching back to 1998 from the European Southern Observatory and the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, and the Calar Alto Observatory in Spain, among many others.

A paper describing the findings was published on Wednesday, July 31, in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics and is available online.

TESS is a NASA Astrophysics Explorer mission led and operated by MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and managed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Additional partners include Northrop Grumman, based in Falls Church, Virginia; NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley; the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts; MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory; and the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. More than a dozen universities, research institutes and observatories worldwide are participants in the mission.

[ad_2]