[ad_1]

From the second we are born, humans start to develop social relationships with individuals and groups starting with parents, family and friends. Similarly, mice are social animals just like us.

Social relationships are a key determinant of social behavior, and numerous studies have shown that when mice experience maternal separation or social isolation during development, their socio-emotional and cognitive behaviors are affected. However, a long-term behavioral analysis of multiple animals in a natural group setting had been required to elucidate the biological basis of the social behaviors developed.

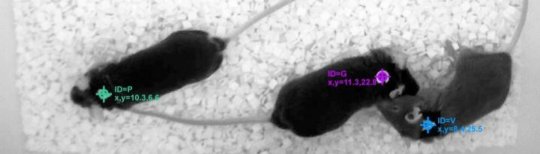

To investigate, a research team led by Professor Masaki Kakeyama of Waseda University developed a novel-video based behavioral analysis system for a long-term behavioral tracking of multiple mice. This software, referred to as the Multiple-Animal Positioning System (MAPS), can automatically and separately analyze the social behavior of multiple mice in group housing.

“Each mouse is individually identified by a mouse ID tag on its back,” explains Professor Kakeyama. “MAPS can then automatically acquire their individual positions based on a pattern-matching technique and save this information to a hard disk drive along with video images. This approach allows MAPS to perform an automated, long-term video tracking of each mouse under social housing conditions.”

In their study, Professor Kakeyama’s team examined how social experience of mice in adolescence affects adult social proximity with unfamiliar mice. First, male mice were either housed in groups or reared in social isolation during adolescence. To detect behavioral differences of mice when interacting with other adult mice from the same rearing background, four mice that had never been co-housed before were placed in an experimental chamber, creating a group-housed mice only housing and socially-isolated mice only housing conditions. Their behavior was then recorded by MAPS.

“Though both groups of mice began to explore the experimental chamber almost immediately, the group-housed mice began to huddle in one location within two hours. On the contrary, the mice reared in social isolation stayed as far away from each other as possible and took two days for all four of them to finally huddle together, showing that adolescent social isolation results in deficient social relationship formation in adulthood.”

In the next experiment, two isolated and two group-housed mice were placed in the same experimental chamber to examine their behavior under mixed housing condition. The group-housed pair type was the fastest to huddle together, the isolated pair type was the slowest, and the heterogeneous pairs were somewhere in between. Interestingly, the isolated mice took less time to form relationships with unfamiliar mice under the mixed-housing than in the isolated-mice-only housing condition, indicating that it is not only individual behavioral traits but also those of surrounding individuals can influence social proximity.

“Additionally, visual observation of video images revealed that the group-housed mice reduced their activity or even became immobile when approached by others,” says Professor Kakeyama. “This suggests that this low activity, or being ‘composed,’ might be an important factor for establishing social relationships.”

The results of this study may not be directly applicable to humans, but Professor Kakeyama hopes that the newly-developed software will contribute to research in help understanding how our minds develop through socialization and advance treatment of psychiatric disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder and social anxiety disorder.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Waseda University. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]