[ad_1]

Species that lay eggs but don’t actively keep watch over them often protect their precious eggs from predators by laying them in communal groups or by fortifying them with toxins. However, protecting these eggs from being devoured by their own kind is a completely different game; the catch is that any anti-cannibalistic strategy needs to be an effective deterrent while remaining nontoxic to the cannibals. In a new study published in the open-access journal PLOS Biology on January 10, Sunitha Narasimha, Roshan Vijendravarma and colleagues report how fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster), which lay eggs communally, use chemical deception to protect their eggs from being cannibalized by their own larvae.

Using a multidisciplinary approach, Dr. Roshan Vijendravarma from the Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Lausanne, Switzerland (currently at Institut Curie, Paris, France) and his team of international collaborators teased apart the chemical, sensory, genetic and mechanistic basis of deception using the Drosophila model system.

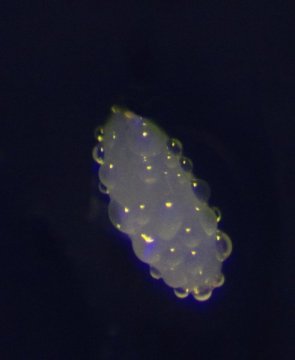

The team was intrigued by the observation that fruit fly larvae, despite their predatory nature, seldom attacked eggs in their vicinity even when deprived of food. While testing for various plausible defense mechanisms, the researchers found that the extremely thin wax layer within the egg shell acts as a protective barrier that prevents cannibalism.

Using high-resolution mass spectrometry to identify the specific molecules involved, the team discovered that the wax layer is composed of a bouquet of sex pheromones originating from both parents, and then nailed the protective effect on a female chemical called 7,11-heptacosadiene (7,11-HD); this pheromone, normally used to spice up the adult flies’ mating, was incorporated into the egg’s wax layer by the mother.

It was already known that the adults need a gene called ppk23 for detecting the 7,11-HD pheromone during mating, so the authors looked to see whether the ppk23 gene played an analogous role in the larvae. They found that the gene was indeed involved in detection of this pheromone in larvae “a different developmental life-stage” but modulates an entirely different behavioral outcome.

Finally, this nontoxic pheromone had an interesting property whereby a coating of 7,11-HD could mask the identity of underlying substances from larvae — even yeast, normally irresistible to fly larvae. In the egg, these maternal hydrocarbons incorporated within the wax layer leak-proofed the egg to prevent desiccation, and by doing so additionally serve as a mask that conceals the egg’s identity from cannibal larvae.

Deception as a defense strategy against predation has evolved independently in diverse species. However, partly owing to our human bias for visual perception, studies on deception have largely focused on vision-based strategies and less on those that dupe the other senses. The team’s findings suggest that chemical deception might be common across the tree of life, especially when predators rely on chemical cues to forage. Furthermore, since studies on animal deception have rarely used powerful model systems like the fruit fly, this study demonstrates how doing so potentially opens the way for research on the sensory, neural, genetic, and mechanistic basis of deception. The in-depth understanding of such strategies is crucial, especially to the fields of conservation, epidemiology, and pest management.

Story Source:

Materials provided by PLOS. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]