[ad_1]

Nature is so complex that natural molecules used for i.e. cancer treatment still can’t be produced by chemical synthesis. Today, major chemical and pharmaceutical companies harvest large amounts of rare plants and seeds in order to extract valuable substances.

But the production methods based on extracts from natural resources are environmentally damaging and often give rise to extensive piles of chemical waste. In addition, there is a great danger that these rare plants will go extinct. The need to find new and more sustainable production methods for these types of medicines has grown since the UN recently adopted new regulations to protect biodiversity and raw materials in third world countries.

“With these new rules, a real alternative is needed if we wish to be able to produce therapeutics to cancer patients or people suffering from mental illnesses in the future,” says Senior Researcher at The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Biosustainability. He is the coordinator of a new big EU Horizon 2020 project called MIAMi, which has just received a grant of 6 million Euro.

Indian snakeroot may be the solution

In many cases, these very complex plant chemicals can’t be synthesized chemically like ‘normal’ pharmaceuticals — it simply has to be a bio-catalytic process.

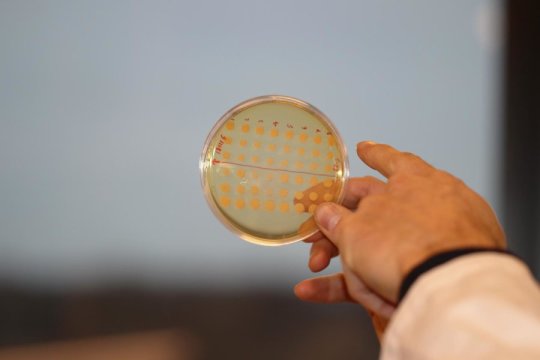

The aim of the MIAMi research project is to provide the pharmaceutical industry with an alternative production route using the cellular workhorse baker’s yeast. To start with, the researchers want to map the so-called biosynthetic pathways of the rare plant Rauvolfia serpentina with the common name Indian snakeroot.

From traditional Chinese medicine, it is known that Indian snakeroot produces molecules with anticancer effect. However, manufacturing the valuable compounds outside the plant is still not possible, because the biosynthetic pathways are unknown.

In short, a biosynthetic pathway is a number of specific genes that code for enzymes, which synthesize a bio-molecule within the cell. Knowing the genetic “route” of the product, makes it possible to move the genes into, for instance, baker’s yeast. The goal is to insert the genes into yeast cells that will act as biological cell factories capable of producing large amounts of these specific therapeutic substances.

Regulations push the industry

One of the partners of MIAMi is the French chemical company Axyntis, which annually imports hundreds of tonnes of plant seed to extract substances for further production of medicine such as tabersonine from the rare plant Voacanga africana. However, the new legislation limits this way of producing medicine.

“The industry knows that they need to change, which these regulations are also a clear signal about. We do not expect to be able to manufacture the products within this project period so that they can compete with current processes, but the alternative is that companies in the future can’t offer the same products to their customers,” says Michael Krogh Jensen.

Over the past 20-30 years, the shelves of bioactive substances in the company’s “chemical libraries” have gradually been used up, and the industry is now in great need of new drugs against new and existing diseases. Therefore, there is also a need to discover new natural occurring molecules with activity against some of the major public diseases such as cancer and mental illness, for example, schizophrenia. Another focus is, therefore, to find new and unknown plant molecules. The project runs for a 4-year period.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Technical University of Denmark. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]